By Åke Hultman

From an article in Photographica World

http://www.pccgb.org

The University of Uppsala imported a Giroux camera dated 1839, and they still have it. In this article Åke Hultman describes what could be the earliest commercially produced Daguerreotype camera in existence.

In 2001 it was just 150 years since the inventor of photography died. LJM Daguerre lived from 1787 to 1851 in France and has been identified as the "Father of Photography". As so often in history, many people were working with the same idea, so others have also laid claim to this invention. Daguerre’s countryman Joseph Nicéphore Niépce cleared the way for the invention and co-operated closely with Daguerre. In England, Henry Fox Talbot was experimenting at the same time with images on paper.

Daguerreotype from the middle

of 1840 by JW Bergström, the

greatest portrait daguerreotypist

in Stockholm

Louis Jaques Mandé Daguerre was a skilful painter and entrepreneur . He operated a popular Diorama with his colleague Charles-Marie Bouton in Paris during the 1820s and 1830s. They exhibited grand illusional paintings up to 14 x 22 m. With aid of controlled lighting they could for instance create a summer idyll which slowly turned into a dramatic landscape with dark sky and thunderstorms. As an artist it was natural for Daguerre to use a camera obscura in his work to draw new views. He was thinking about how to capture the view from the camera obscura as early as 1827. After considerable research, and a significant contribution from his partner Niépce, by 1837 had he succeeded in fixing the image so that it did not fade in daylight.

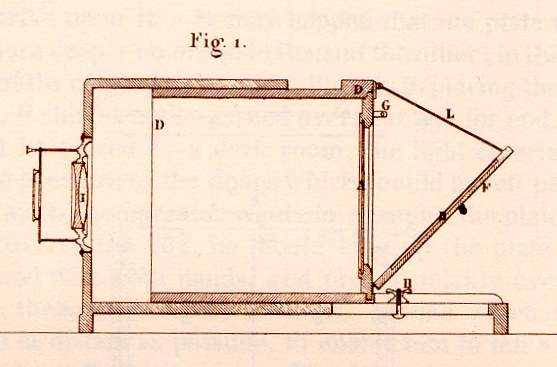

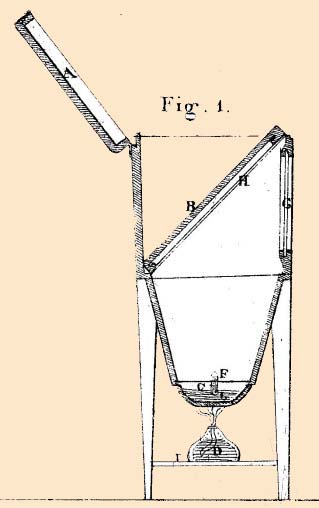

A Giroux Daguerre camera in cross-section according to the description.

Daguerre’s

invention was presented to the French Academy of Sciences by the physicist Francois Jean

Dominique Arago, on the 7th of January 1839. Only three weeks later the news reached

Sweden, in the Aftonbladet under the headline: “A landscape’s depiction

by its own reflection”. The American Samuel Morse visited Paris in March 1939 to

patent his electric telegraph. He visited Daguerre to look at the new method of fixing the

image in a camera obscura. Morse was impressed; he writes to his brother: “It is one

of the most beautiful discoveries of the age.” Whilst Daguerre was visiting Morse at

his hotel the Diorama caught fire and was totally destroyed. The time for the Diorama had

passed and it was never rebuilt. Full details of the invention were published on 19th

August in the same year. Niépce and Daguerre were awarded an annual pension for life and

the invention was given to the public – except in Britain, the largest export market

at the time.

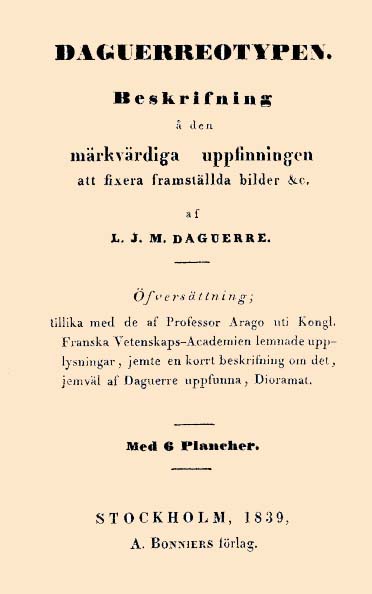

Daguerre’s description came out in Sweden as early as December 1839

The demand for daguerreotype equipment was enormous. A camera was designed by Daguerre and made by his brother-in-law Alphonse Giroux. Giroux got half the profit, Daguerre and Niépce got 25 percent each. The great optician Chevalier expressed his disappointment when he was not asked to make Daguerre’s camera - “An optician was needed, a stationer was chosen”. His disappointment was somewhat abated when he was allowed to make the optics. The lenses were slow, and with the relatively insensitive plates the exposure time was about 10 to 20 minutes.

In a few months Daguerre and Giroux sold all the cameras that they had made. Many instrument makers copied the camera. If you could not afford a camera you purchased Giroux’ description, which was soon published in 32 different editions in many languages. The whole outfit including camera, box for polished plates, box for iodising, mercury box, spirit lamp, buff stick and various chemicals weighed about 50kg. By December 1839 Daguerre’s method was described in Swedish and the publisher “Bonniers Förlag” also sold a complete outfit.

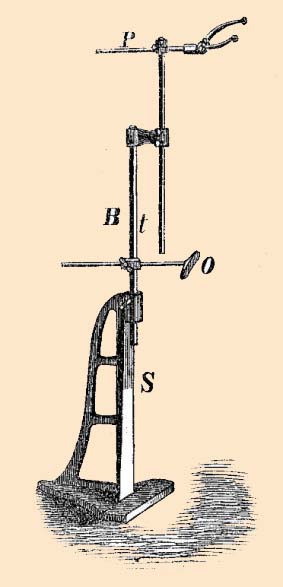

Because of the long time of exposure

a headrest had to be used.

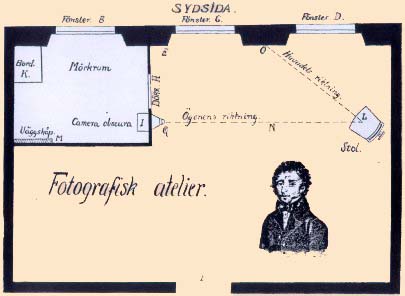

In Daguerre’s description, five operations are described to make a daguerreotype: polishing, iodising, exposure, developing and fixing. One of the drawbacks with the invention was the long exposure time. Early daguerreotypes are therefore often images of landscapes, buildings and still-lifes. By1840 it was possible to take portraits with aid of faster optics by Petzval, and the plates were also made more sensitive by treatment with bromine vapour. Cameras were soon made with smaller formats such as half plate and quarter plate, and in this way the weight was also reduced. Many artists saw that portrait painters were threatened by photography and purchased the new equipment, and became travelling daguerreotypists.

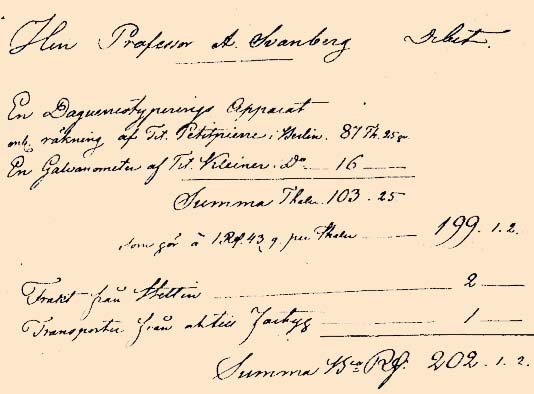

In 1841 Professor A. Svanberg in the Department of Physics at Uppsala University in Sweden ordered an outfit from the instrument making firm Petitpierre in Berlin]. The bill is still preserved in the archives of Uppsala University. It was at the time a relatively major purchase. The equipment was sent by boat from Stettin to Stockholm. The freight from Stettin cost 2 Thaler and transport from and to the boat 1 Thaler. The equipment cost 87 Thaler and 25 groschen, or about 168 Swedish riksdaler, today about $1500. The camera was damaged in transit but was delivered in 1842. The camera, iodising box and mercury box make up one of about twelve sets of equipment, which are still preserved in the world today. Its genuineness is confirmed by the plaque at the side of the camera. There are Daguerre’s signature, Giroux’ seal and the year 1839. This camera is the first commercially manufactured model and is from a photo-historical point of view a most important camera. The text on the plaque is:

Photographic studio according to Netto 1842.

The bill is preserved at The Archives of the University of Uppsala. The bill is dated 19th of November 1841 and is signed by Fab. Wrede in Stockholm

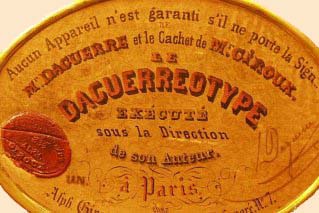

”Aucun Appareil n’est garanti s’il ne porte la Sign.. de Mr. Daguerre et le Cachet de Mr. Giroux. Le DAGUERREOTYPE, exécute’ sous la Direction de son Auteur, à Paris, chez Alph.Giroux et Cie., Rue du Coq. St Honore’ No7”.

“The warranty of the apparatus is not valid if it does not carry Mr Daguerre’s signature and Mr Giroux’ seal. The DAGUERREOTYPE Made under supervision by its originator by Alph. Giroux and Company, Rue du Coq. St Honore’ No 7 in Paris”

Text on the seal: ”DAGUERREOTYPE 1839 Alph. Giroux.”

To the left Giroux’ seal on the plaque and the mark UN. To the right Daguerre’s signature.

The iodizing box and the mercury box are also preserved. With the mercury box is still the original thermometer marked “Alph. Giroux”. The camera is made for plates with size 164 x 216 mm, the same size as Niépce’s first pewter plates. Behind the ground glass is a 45 degree mirror in to give a right-reading image. By sliding the rear box forward and backwards the camera can be focused, and also the lens is moveable in its mount for fine focusing. The shutter is simply a disc on the front of the lens which is moved out to make an exposure. The baseboard of the camera is 380 x 513 mm. The plate holder, which is not preserved, had double hinged doors, which protected the plate from light before and after exposure. The doors could be opened from the rear of the plate holder using brass quadrants. In this camera are a few brass details which seem to be the remains of an experiment. In the Swedish translation by Daguerre’s description the translator made a remark about a device to facilitate the determination of time of exposure. It is possible that it is this experiment that was tried. The camera is made from pine, edged with walnut. The central front panel is walnut or a similar wood.

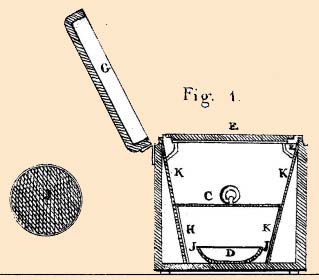

Mercury box according the description

from 1839.

The iodizing box and the mercury box which also are preserved by The Department of Physics at Uppsala University.

Iodizing box according the

description from 1839.

Note that the front of the lens is engraved “LE DAGUERREOTYPE par Alph Giroux”. That means the camera is an early specimen, as later cameras have the text “LE DAGUERREOTYPE chez Alph Giroux et Comp”. According to the photohistorians Helmut and Alison Gernsheim, Giroux exported the first equipments to Louis Sachse and Edward Petitpierre in Berlin. At the right of the seal Giroux has numbered the cameras he manufactured. The specimen in Uppsala is numbered Un (un means one in French). It is possible that this camera could be the very first camera that Giroux exported.

The lens is fastened to the front with six screws. There are some holes which reveal that the camera has had another lens. The extant lens is a plano-convex achromat with a focus of 415 mm and with an effective aperture of f/15. One face of the lens is almost flat and this side is turned to the subject. The demand for the camera was huge. When Chevalier was not able to deliver enough lenses Lerebours and other Paris opticians were asked to make lenses which could fit the camera. Chevalier’s lens was a meniscus achromat but the other opticians made plano convex lenses. On the edge of the lens mount is engraved in German: “Apparat von Giroux Paris”.

It is possible to adjust the focus in its mount

Already in 1841 when the camera was delivered, the Giroux camera was beginning to be out of date. Ségiur made an outfit in November 1839 which was only a third of the weight of Giroux’ equipment. Wolcott constructed a camera with a large metal concave mirror. Chevalier also made a collapsible camera with better optics. His cameras for smaller sized plates made it possible to take portraits, as did also Voigtländer’s completely metal camera with its fast Petzval lens. It was a great sensation that nature itself could produce an image when Daguerre1839 presented his method. Today photography is natural. L J M Daguerre died on the 10th July 1851, the same year the wet collodion process was invented by Frederick Scott Archer. Daguerre’s process was virtually abandoned by the end of the1850s but his name will always be connected with the birth of photography.

Literature:

Helmut and Alison Gernsheim,

L.J.M. Daguerre, The History of the Diorama and the Daguerreotype. 1968

Beaumont Newhall, Daguerre, Historical &Desrciptive Account of the Various processe of

the Daguerreotype. 1971

Beaumont Newhall, The History and Prctice of the Art of Photography, Snelling Reprint 1849, 1970

Per Hemmingsson, Fotohistoriskt, 1970. Sweden

Flemming Berendt, Daguerreotypikameraets Historie. Denmark